It’s possible that major players in the tech industry, with the cooperation of the U.S. Government, have found a creative method for boosting internet availability in rural or impoverished communities, thanks to “white space.”

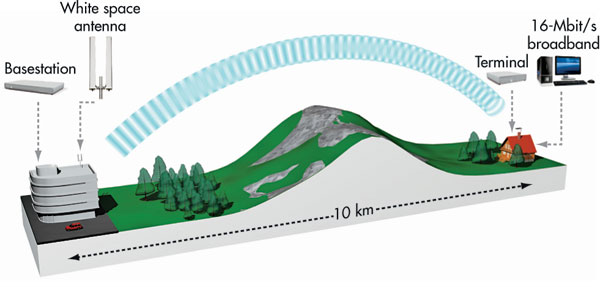

White space is known by various nicknames, including the “TV Band” or “Super Wi-Fi”, but it essentially refers to unused parts of the old analog TV broadcast bands that originally existed as buffer zones to prevent nearby broadcasters from interfering with each other’s signals. Google co-founder and former CEO Larry Page even referred to white space as “Wi-Fi on steroids” because these spectrums allow for data transmissions over greater distances than standard Wi-Fi. Because the white space spectrum falls in lower frequencies than cellular communications systems, white space transmissions can more easily penetrate through buildings, foliage, woodlands, and even the walls of people’s houses, making it all the more valuable to customers living in rural areas. According to PCWorld, the Nuels Company in the UK claims to have transmitted 16 MB of data per second (16 Mbps) across 10 kilometers, making white space Internet transmission comparable in speed to so-called 4G wireless networks in the US.

White space was largely unused until 2008, when the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) approved a law that allowed private technology companies and individuals to make use of the space for broadcasting internet signals. Prior to this ruling, white space acted a neutral zone to protect broadcast TV signals from interference. The FCC approval meant that companies like Google and Microsoft found their visions of unlicensed, free networks effectively endorsed by an erstwhile (and future) adversary. FCC Chairman Kevin Martin even told USA TODAY that the move marked a “significant victory for consumers,” and went on to say that the “ability to have Wi-Fi-like connectivity, at faster speeds and greater range” would effectively help more Americans connect to the Internet, regardless of income or geographical location.

Unsurprisingly, many key players in the tech industry joined Google and Microsoft in being vocally supportive of FCC’s decision from the beginning; the Information Technology Association issued a statement after the 2008 ruling to say that “this spectrum should become fertile ground for innovation, potentially offering consumers and companies an unlimited variety of applications, devices, networks and more,” and Motorola, Dell, IBM, and HP also offered positive statements about the opening of the spectrum.

In 2009, the first public white space network was launched in Claudville, Virginia — a town with a population of 900. Claude was home to a single high school, and the nearest town (Ararat) was just over five miles away. A channel database, required so that white space devices can query it to ensure they’re transmitting on a free frequency, was provided by Spectrum Bridge, and that company successfully used white spaces to link the center of town with internet access which could then be distributed via traditional Wi-Fi. The director of the Claudville Computer Center, Roger Hayden, said that he was thrilled by the white space test, saying he “had been trying to get local service providers to bring broadband into Claudville for over 6 years with no success.”

This trial clearly demonstrated the potential social utility of white space – connecting those who had never been connected at a fraction of the cost of installing cables or fiber optic lines to link outlying areas to existing networks.

In 2010, shortly after Claudville went online, Wilmington, NC became a white space test site. Incidentally, PCWorld reported the heavily forested Wilmington had also been the first city in the U.S. to make the switch to from analog to digital TV. Because that transition had been fairly seamless, the FCC thought the city was the ideal candidate for this round of tests. According to Ars Technica, one side effect of the Wilmington test that manifested very early on was the unprecedentedly large number of children who received laptops for Christmas that year.

People living in rural areas of the US are used to having difficulty finding reliable Internet service at all; cable and cellular connections have mostly not been feasible, and so most consumers have had to rely on satellite Internet for any semblance of the speed and connectivity available in urban centers. Hughesnet, a subsidiary of the company founded by American innovator Howard Hughes himself became the first company to offer consumers satellite based Internet service for their homes in 1996, with others like Dish and Wild Blue following close behind, and these companies have been able to provide coverage to most rural areas in the states. But considering the many inefficiencies of satellite Internet (signals can be too easily interrupted by weather or even just high winds, and setting up the often unreliable hardware is cumbersome), not to mention the high cost of equipment and monthly bills, white space Internet should become a very desirable alternative for rural Americans.

In July of this year, Eweek reported that the FCC had given Google official certification to operate as a white space database administrator. This means that Google will have the authority to speak with Internet service providers about which spaces within the white band are available for Internet use – much like the aforementioned Spectrum Bridge in Virginia, but on a national level. Alan Norman, representing Google’s Access team, wrote on the company’s official blog that with certification from the FCC, Google would be able to “do more to help make spectrum available. We are ready to work with leaders in the wireless industry – those developing certified devices that can talk to a database – to help them gain access to the TV white spaces spectrum to help bring new technologies and services to market.”

The results from both North Carolina and Virginia were encouraging, and now, Google is exploring the implications of white space internet for rural communities throughout the world.

According to Eweek, Google’s analysts determined that there is white space available for Internet transmissions in parts of Cape Town, South Africa, and Dakar, Senegal. Google even launched a white space trial program in South Africa in March, wherein the company provided 10 schools in Cape Town with a broadband connection via white space transmissions. Fortune Mgwili-Sibanda, a representative of Google South Africa, said that, beyond whatever good the technology could do for developing countries, white space Internet could also benefit city dwellers by “expanding coverage of wireless broadband in densely populated urban areas.”

The results from both North Carolina and Virginia were encouraging, and now, with Google exploring the implications of white space internet for rural communities throughout the world, it appears that these technological advances could yield tremendous good for those who have, up until this point, been denied access to the internet — which is itself, potentially the greatest, and most ubiquitous, resource of the modern age.

This is a guest post by Kate Voss.